May 31, 2010

The Strain Toward Transcendence: Axial Age Values

In the span of just a few short centuries, between roughly 750-350 BCE, human society in Europe and Asia was transformed by an array of original thinkers and new systems of thought never seen before in history. The list is astonishing: Lao Tzu[1] and Confucius in China; the Buddha and the Upanishads in India; Zoroaster and the Old Testament in the Middle East; and Plato, Sophocles and so many other great minds in Ancient Greece.

The German philosopher, Karl Jaspers, was the first to remark on this phenomenon in his book, The Origin and Goal of History, published in 1949. He called it the Axial Age, because as he saw it, this period was like a great axis, when “we meet with the most deep cut dividing line in history. Man, as we know him today, came into being.”[2] Since then, the Axial Age has been a favorite subject of books and symposiums, with scholars trying to figure out exactly what was happening during those times, and why.

A general consensus has evolved that the new systematic ideologies that arose, speculating on mankind’s place in the cosmos and offering new sets of values for how we should interact with each other, were a result of the greater size and complexity of society. Cities were getting bigger; empires covered vast tracts of land, incorporating multiple diverse cultures. Author Robert Wright offers a good summary of some of these changes:

Certainly [the first millennium BCE] is a millennium of great material change. Coins are invented, and appear in China, India, and the Middle East. Commercial roads grow, crossing political bounds. In the course of this millennium, markets… supplant state-controlled economies. Cities get accordingly big and vibrant and, in many cases, more ethnically diverse… [M]ore and more people found themselves in an environment radically unlike the environment natural selection had ‘designed’ people for.[3]

But in fact, as I’ve described in a previous post on agricultural values, people had already evolved new sets of values for thousands of years that separated them from the hunter-gatherer values we’d been selected for by evolution. So to be precise, the Axial Age, in my view, represents a second step away from that original value-constellation.

But there’s a big issue that’s not explained by the simple theory of society getting bigger and more complex. The Axial Age revolution didn’t happen in all the great civilizations of Eurasia. In fact, it completely bypassed the two civilizations that were among the greatest of them all: Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt, as has been noticed by classical scholar Benjamin Schwartz among others.[4] Why was that?

My own theory is that Mesopotamia and Egypt were simply too stable and monolithic. Things generally worked there. Sure, there were all kinds of crises and invasions, famines and catastrophes. But through all their dynastic turbulence, the fact remains that both the Mesopotamian and Egyptian civilization and culture continued in a fairly stable form for thousands of years. Meanwhile, in each of the areas where Axial Age values did erupt, societies were enduring centuries of social and political instability and political fragmentation.

In China, Lao Tzu and Confucius emerged during an era known as the Warring States Period, when regional warlords were continually jostling for power with each other. This only ended with the unification of China under the Qin dynasty in 221 BCE.

Not too much is known about the political structure in Northeast India at the time that produced the Upanishads and the Buddha, but the celebrated German Indologist Hermann Kulke describes it as a time when Aryan settlers from the northwest were bringing their ancient Brahmanical traditions into contact with the indigenous populations. As he describes it:

Nowhere in the whole of Northern India the contrast and even opposition between Brahmanical and monarchical institutions on the one side and indigenous and heterodox cults and pre-monarchical institutions on the other side seem to have been more striking than in the eastern countries.[5]

And once again, politically, the area was fragmented into a collection of “strong chieftaincies and small kingdoms.”

The picture of instability and fragmentation is the same when you consider the Hebrew experience of constant invasions, destruction of their temple, and exile to Babylon. And finally, while the Greeks were fortunate to avoid the catastrophes of the Hebrews, their culture was highly fragmented politically, with their city-states constantly at war with one another, uniting only temporarily to face the Persian threat from the east.

It took the existential angst of seeing communities continually beset by war and uncertainty, along with a lack of a central, unifying socio-cultural force, to generate the intellectual ferment that could give rise to the great breakthroughs of thought characterizing the Axial Age. So what were these breakthroughs? And did they share any common features, or where they all unique?

Probably the most important feature shared by all these Axial Age breakthroughs in thought was what Benjamin Schwartz has called a “strain toward transcendence.” Here’s how he describes it:

If there is nevertheless some common underlying impulse in all these “axial” movements, it might be called the strain toward transcendence… a kind of standing back and looking beyond – a kind of critical, reflective questioning of the actual and a new vision of what lies beyond.[6]

Following Schwartz, we can think of Axial Age philosophers observing the catastrophes occurring in their societies as a result of people following the primary values of the agricultural age, which I refer to as the Age of Anxiety. These values extolled wealth and social hierarchies, glorified destruction of enemy nations, and emphasized propitiation of local, ancestral gods as a means to success. Perhaps each of the foundational philosophers asked themselves how to transcend these destructive values, how to find a system of thought that could provide greater meaning and fulfillment to their communities.

If this was their aim, they seem to have succeeded, for in each Axial Age breakthrough we see a universalization of cosmological explanations and a broadening of the moral community to extend beyond the borders of a particular nation or empire. As the philosopher of comparative religions, Huston Smith, has noted, each Axial Age breakthrough system established a form of the Golden Rule, to do unto others as you would want them to do to you. In his view, “these counsels of concern for the well-being of others were one of the glories of religion during its Axial period.”[7]

While each Axial Age breakthrough had this transcendent characteristic in common, their other notable element was how unique each new systematic philosophy was. For the first time in history, different cultures established their own intellectual foundations for a worldview and began to evolve their thought traditions accordingly. In China, India and the Eastern Mediterranean, three very different traditions evolved, each of which would affect the future course of their region’s history.

In China, the Taoist and Confucian traditions agreed on the underlying nature of the Tao as an intrinsic, dynamic force that harmonized heaven and earth. They disagreed on how to interpret this force, whether to emphasize individual fulfillment or social harmony as a way to live one’s life, but they didn’t question the underlying cosmology.

In India, the Upanishads began to develop a systematic interpretation of the cosmos, linking the individual’s soul, or atman, with the universal being, or Brahman, and describing a spiritual path whereby a person could unlearn the habits of the mundane world and realize this universal linkage between himself and the universe. The Buddha’s philosophy was, in some senses, in radical opposition to the Upanishadic doctrines, emphasizing a middle way between the alternatives of holy asceticism and worldly suffering. However, even this radical departure continued to accept some underlying cosmological foundations of the Upanishads, specifically the belief in the soul’s reincarnation and the ultimate goal of release from the continual cycle of rebirths.[8]

In the Eastern Mediterranean, the two major Axial breakthroughs of Hebrew monotheism and Greek rationalism at first seem very different. They do, however, share a structural element that underlies both the Christian and Islamic cosmologies, forming the foundation of the monotheistic worldview that has since dominated vast regions of the world. This structural element can be summarized as the world’s first truly dualistic worldview, a universe comprised of two utterly different dimensions: an eternal dimension that is sacred, immaterial and unchanging; and a worldly dimension that is profane, material and mortal. This same dualism is applied to both the external world and to the internal world of human nature, splitting the human being into two: a body and a soul.

This extreme dualism[9] is so pervasive in our modern world that many of us just take it for granted without even questioning its origins. But in fact, it’s unique in the history of human thought, and following the conquests by Christian and Islamic powers over so much of the world, it’s had a powerful effect on billions of lives and the direction of our entire world. The next post will examine the sources and implications of this relatively new and powerful layer of human values.

[1] In fact, most scholars nowadays believe that Lao Tzu was not a real person, but that the Tao Te Ching was a compilation from multiple authors.

[2] Cited by Watson, P. (2005). Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud, New York: HarperCollins.

[3] Wright, R. (2009). The Evolution of God, New York: Hachette Book Group, 238-9.

[4] Schwartz, B. I. (1975). “The Age of Transcendence.” Dædalus, 104(2), 1-7.

[5] Kulke, H. (1986). “The Historical Background of India’s Axial Age”, in S. N. Eisenstadt, (ed.), The Origins & Diversity of Axial Age Civilizations. Albany: State University of New York Press.

[6] Schwartz, op. cit.

[7] Smith, H. (1982/2003). Beyond the Postmodern Mind: The Place of Meaning in a Global Civilization, Wheaton, IL: Quest Books.

[8] Whether the Buddha himself accepted the doctrine of reincarnation, or whether his followers infused the Buddha’s original ideas with some of the trappings of the contemporary cosmological speculations, remains a controversial topic. See Batchelor S. (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist, New York, NY: Spiegel & Grau.

[9] I call it “extreme dualism” to differentiate it from a fuzzier kind of “dualism” intrinsic to human thought, whereby a certain “essence” or “spirit” is seen to exist separately from the material body. However, in earlier forms of “dualism,” the spirit is still thought to have a material existence, frequently associated with the breath, the wind, or something with a much finer essence than the body.

February 22, 2010

Stages in the tyranny of the prefrontal cortex: an overview

[Click here to open pdf file: “Stages in the Tyranny of the Pfc” and view the table that accompanies this post.]

In this blog, I propose that the prefrontal cortex has created an imbalance within our human consciousness, gaining power over other aspects of our cognition. I’ve called this situation a “tyranny.” That’s a pretty dramatic word, and I’ve offered a detailed review of why I think it’s appropriate.

In this post, I’m going to trace a high-level overview of the historical stages I see in the pfc’s rise to power. It will be much easier to follow this post if you click here to open a pdf file in another window, containing a table that summarizes what I’m describing. If you can keep both windows open, you can follow what I’m describing more easily.

For each stage of the pfc’s rise to power, I’ll briefly describe the main human accomplishments and primary new values arising from that stage. Also, I’ll touch on the changing view of the natural world. Whenever you want to drill a little deeper, click on the section’s title (or the links in the pdf file) to get you to a blog post that describes the pfc-stage in some more detail. I’ll be continually adding more detail on this blog, so keep posted.

Pfc1: Stirrings of Power

The pfc’s stirrings of power began with the emergence of modern Homo sapiens, around 200,000 years ago. These ancestors of ours were all hunter-gatherers. Basic tools and fire had already been mastered by previous Homo species (such as Homo erectus). But Homo sapiens began a symbolic revolution which erupted around 30,000 years ago in Europe, comprising symbolic communication in the forms of art, myth, and fully developed language.[1] The prevailing metaphor of Nature was probably something like a “generous parent.” Uniquely human values began developing, such as “parochial altruism” (defend your own tribe but fight others), “reciprocal generosity” and fairness.[2]

Pfc2: Ascendancy to Power

Roughly ten thousand years ago, in the Near East, some foragers stumbled on a new way of getting sustenance from the natural world and occasionally began to settle in one place. Animals and plants began to be domesticated, evolving into forms that were more advantageous for humans and relied on human management for their survival. Notions of property and land ownership arose. Hierarchies and inequalities developed within a society, along with specialization of skills (including writing). Massive organized projects, such as irrigation, began to take place. Cities and empires soon followed.

New sets of values arose with these sweeping changes in human behavior. Property ownership and hierarchies elevated the social values of wealth and power. Patriarchy became a driving force, leading to increased gender inequality and the commoditization of women. People’s identity began expanding beyond kin and tribe, to incorporate national identity.

The natural world was increasingly seen through the metaphor of an ancestor/divinity that needed to be worshipped and propitiated. Nature could cause devastation as well as benefits to society. Human activity was seen as integral to maintaining the order of the natural world.

Pfc3: The Coup

In the Eastern Mediterranean, about 2,500 years ago, a unique notion first appeared: the idea of a completely abstract and eternal dimension in the universe and in each human psyche, which was utterly separate from the material world of normal experience. Humans had always posited other-worldly spirits and gods with different physical dynamics than the mundane world. But these spirits were conceived along a continuum of materiality. Now, for the first time, the idea of a universal, eternal God with infinite powers arose, along with the parallel idea of an immaterial human soul existing utterly apart from the body.

Christianity merged the Platonic ideal of a soul with the Judaic notion of an infinite God to create the first coherent dualistic cosmology. Islam absorbed both of these ideas into its doctrines. Together, Christianity and Islam conquered large portions of the world and brought their dualism along with their military power.

For the first time, people identified themselves with universal values (such as salvation of the soul), which were seen as applying even to other groups who had no notion of these values. Increasingly, mankind was viewed as separate from the natural world. Following Genesis, Man was seen as having a God-given dominion over the rest of creation.

Pfc4: The Tyranny

In the 17th century, a Scientific Revolution erupted in Europe, leading to a closely linked Industrial Revolution, beginning a cycle of exponentially increasing technological change that continues to the present day. Although the seeds of scientific thinking could be traced back to the 12th century (and even to ancient Greece), a radically different view of mankind’s relationship to the natural world caused a uniquely powerful positive feedback cycle in social and technological change.

Nature was increasingly seen as a soulless, material resource available for humanity’s consumption. The natural world and the human being were both seen through the prism of a “machine” metaphor.

Multiple new values arose, that were seen to be universally applicable, derived from newly developed intellectual constructs, such as: liberty, reason, democracy, fascism, communism, capitalism. These values all shared the underlying assumption that natural resources were freely available for human consumption, and differed in their proposed division of power and resources within human society.

[1] The precise timing of these developments continues to be fiercely debated. The biggest open issue of all is the timing of language (anywhere from one million to one hundred thousand years ago), and whether a proto-language existed for a long time before modern language developed.

[2] Some of these values have been seen in modern chimpanzees and bonobos, but they are far more developed in humans.

February 4, 2010

Monotheism By Numbers?

Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia

Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia

By Jean Bottéro

Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2001

Elsewhere on this blog, I argue that dualism and monotheism have caused a profound change in our collective consciousness over the past two thousand years. Underlying the monotheistic/dualistic thought pattern is the notion that two different dimensions exist: a worldly dimension of the body, and an eternal dimension of the soul. If my argument is correct, then prior to the advent of Platonic dualism and Judeo-Christian monotheism, people around the world must have viewed their cosmos with blurrier distinctions, not conceiving of two utterly different dimensions.

Jean Bottéro’s Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia is an authoritative but accessible assessment of one of the major worldviews that existed before the advent of dualism and monotheism. Bottéro is “one of the world’s foremost experts on Assyriology,” having studied it for over fifty years and the book certainly delivers on its title, reviewing Mesopotamian religion from the perspectives of religious sentiments, conceptual representations, and behaviors.

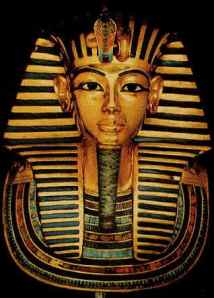

So, does Bottéro’s review support my position? I think it does, especially when you compare some of the themes he describes in Mesopotamia to the contemporary religious worldview in Ancient Egypt. Although these two civilizations come from very different traditions, it’s fascinating to see how some of the underlying structural aspects of their worldviews are at the same time so similar to each other, and so fundamentally different from the later monotheism of Christianity.

One of the intriguing dynamics shared by both Mesopotamia and Egypt was the tendency to pray to a particular god as if he or she were the only god, or at least the only god that mattered. This is known either as “monolatry” (from the Greek “single worship”) or “henotheism” (from the Greek “one god”). Bottéro describes it as “a profound tendency… to encapsulate all sacred potential into the particular divine personality whom [the Mesopotamians] were addressing at a given moment.” He gives a few examples:

Anu was ‘the prince of the gods,’ but so was Sîn. The ‘Word’ of each god was ‘preponderant’ and ‘was to be taken above those of the other gods,’ who were subjected to it, ‘trembling.’ Each god was ‘the ruler of Heaven and Earth,’ ‘sublime throughout the universe,’ supreme and ‘unequaled’.

Over in Egypt, they were doing just the same thing. Egyptian scholar Erik Hornung describes how, “in the act of worship, whether it be in prayer, hymn of praise, or ethical attachment and obligation, the Egyptians single out one god, who for them at that moment signifies everything.”[1]

At first sight, this seems like a form of proto-monotheism, but Bottéro takes pains to deny that, asserting that “contrary to what has sometimes been believed… a true monotheism could scarcely be born out of this religion, which assuredly never ceased to intelligently rationalize and organize its polytheism, and which, in truth… never departed from it.”

One of the crucial ways in which Mesopotamian and Egyptian cosmologies – indeed the cosmologies of every historic polytheistic culture worldwide – differed from monotheism was their acceptance of the gods of other cultures. This goes beyond the notion of religious tolerance. It was inconceivable to either the Mesopotamians or Egyptians to question the existence of another region’s gods. Gods presided over specific areas, so it was quite consistent with polytheistic beliefs to worship your own gods even while your neighbors – and perhaps your enemies – were worshiping theirs. Bottéro gives a helpful analogy, comparing this view to how we might think of political offices in the modern world:

The foreign pantheons were tacitly considered as what they were: the product of different cultures, with their members playing a role analogous to that played by the indigenous gods of Mesopotamia. It was as if, on the supernatural level, they had recognized the existence of a certain number of divine functions, of which the titularies bore, depending on the lands and the cultures, different names and personalities – a bit like political offices, which were pretty much the same everywhere; only their names were different, as were those of the individuals who held the offices.

With this analogy, we can see how denying the existence of another region’s gods would be as nonsensical as Hillary Clinton traveling to China and denying that they have a Communist party. Again, the Egyptians shared the same mindset. Egyptian scholar Jan Assmann tells us how:

The different peoples worshipped different gods, but nobody contested the reality of foreign gods and the legitimacy of foreign forms of worship. The distinction I am speaking of [monotheistic true/false] simply did not exist in the world of polytheistic religions.[2]

Perhaps the most subtle yet profound disconnect between early polytheistic worldviews and monotheism was their lack of sharp distinctions between the realms of human and divine. Gilgamesh was a mortal, an ancient king of Mesopotamia, and yet his parents, Lugalbanda and Ninsuna, were semi-divine. The Epic of Gilgamesh tells us that “two-thirds of him is god; one-third of him is human,” leading Bottéro to conclude that “the notion of ‘divinity’ was somewhat ‘elastic.’” Once again, over in Egypt, Assmann tells us, we see an “interpenetration of the cosmic, the sociopolitical, and the individual,” such that “the Egyptians did not view their gods and goddesses as beyond nature, but rather in nature and thus as nature.”

If monotheism represents such a vast disconnect from previous polytheistic thought, it’s reasonable to ask what were the underlying factors that led to this great shift. My proposal is that certain functions mediated by the human prefrontal cortex – the capacity for abstraction and symbolization – gained increased prominence in our collective consciousness until they became values in themselves: the pure abstraction of an eternal, infinite God. Interestingly, Bottéro identifies the seeds of this transformation in Mesopotamian culture: not in their polytheism, but rather in their attribution of divine value to their number system.

Bottéro notes how the number 60, the “supreme round number” (the Babylonians used the decimo-sexagesimal system), was attributed to Anu, “the supreme chief of the divine dynasty”, and 30 to Sîn, the moon god. He explains how they were evaluating the divine nature of the gods by “assigning them the most immaterial and abstract concepts, the least ‘tangible’ they had available – numbers – as if they knew that to speak righteously of the gods it was necessary, insofar as was possible, to go beyond the material and carnal reality of humans.”

This “attempt to stress both the transcendence and the mystery of the supernatural world” might possibly be seen as a precursor to the Pythagorean assignment of transcendent meaning to numbers, which became a foundation for Plato’s dualistic worldview. And the rest, as they say, is history.

[1] Hornung, E. (1971/1996). Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many, J. Baines, translator, New York: Cornell University Press.

[2] Assmann, J. (1984/2001). The Search for God in Ancient Egypt, D. Lorton, translator, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

January 4, 2010

The Bible Unearthed

The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of its Sacred Texts,

The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of its Sacred Texts,

By Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman

New York: Touchstone, 2002

Despite (or perhaps because of) the tremendous power and influence of the Bible in shaping our Western cultural tradition, it’s only been in recent decades that archeologists have made much progress in answering basic questions about it: Who wrote it? When did they write it? How much of it is true? The Bible Unearthed by Finkelstein and Silberman does a powerful and effective job in putting together recent findings to create a satisfyingly credible narrative.

The book’s main theme is that “much of the biblical narrative is a product of the hopes, fears, and ambitions of the kingdom of Judah, culminating in the reign of King Josiah at the end of the seventh century BCE.” We see how the events described in the Bible close to that time are borne out to a large extent by archeological findings, but as you go further back into the past, there’s not much to validate the literal veracity of the biblical stories. As the authors put it:

Much of what is commonly taken for granted as accurate history – the stories of the patriarchs, the Exodus, the conquest of Canaan, and even the saga of the glorious united monarchy of David and Solomon – are, rather, the creative expressions of a powerful religious reform movement that flourished in the kingdom of Judah in the Late Iron Age.

A theme I believe is important in the rise of monotheistic religion is the natural linkage to monotheism of both authoritarianism and intolerance. In Finkelstein and Silberman’s narrative, this linkage becomes very clear. They see the adoption of monotheism by the kingdom of Judah as being driven in large part by the need for a centralized and unified political authority. Prior to this time, Judah was like any other place in the ancient world, where “religious ideas were diverse and dispersed,” with countless fertility and ancestor cults in the countryside” and “the widespread mixing of the worship of YHWH with that of other gods.” However, after the fall of Samaria, the centralized authority in Jerusalem had a “new political and territorial agenda: the unification of all Israel.”

Unfortunately, this “extraordinary outpouring of retrospective theology” introduced the same monotheistic intolerance that our modern world continues to suffer from. As Finkelstein & Silberman describe it, “in order to effect a thorough cleansing of the cult of YHWH, Josiah launched the most intense puritan reform in the history of Judah.” They quote from 2 Kings to show how zealously Josiah established his new centralized dogma — and sadly this is one of the more believable parts of the Bible because of the proximity of the events to the time of writing:

The king commanded the high priest Hilkiah… to bring out of the temple of the Lord all the vessels made for Baal, for Asherah, and for all the host of heaven; he burned them outside Jerusalem in the fields of the Kidron, and carried their ashes to Bethel. 5He deposed the idolatrous priests whom the kings of Judah had ordained… He brought out the image of* Asherah from the house of the Lord, outside Jerusalem, to the Wadi Kidron, burned it at the Wadi Kidron, beat it to dust and threw the dust of it upon the graves of the common people… He slaughtered on the altars all the priests of the high places who were there, and burned human bones on them. Then he returned to Jerusalem.

With a beginning like this, is it any wonder that Jerusalem is still one of the centers of global intolerance and hatred?

Finkelstein & Silberman go to great pains, however, to try to offer a balanced perspective on the moral implications of their findings. Clearly, they don’t want the scientific rigor of their analysis to be colored by the emotions from all sides of the religious debate. They point out that the book of Deuteronomy, written for the most part by Josiah’s reformers, “contains ethical laws and provisions for social welfare that have no parallel anywhere else in the Bible” and calls for “the protection of the individual, for the defense of what we would call today human rights and human dignity.”

On the other hand, we see similar drives for social equity in other groundbreaking traditions of the time, such as Solon’s reforms in Athens, and the old Akkadian notions of andurarum (“freedom”) and misharum (“equity”) which appear as loan words in the Old Testament and may have been the source of Josiah’s ethics.[1] Somehow, though, the Greeks and the Mesopotamians managed to get their ideas across without resort to the intolerance of monotheism.

It would be nice to think that detailed, rigorous studies such as this book could have an impact on the fundamentalist tides surging through our modern world. It may not stop any raging preacher calling on his flock to fulfill “God’s commandments,” but at least it offers an accessible and authentic account of the source of the Old Testament for those who take the effort to try to sort things out for themselves.

[1] For a full discussion of these Akkadian concepts, see Lamberg-Karlovsky, C. C. (2000). “The Near Eastern ‘Breakout’ and the Mesopotamian Social Contract”, in M. Lamberg-Karlovsky, (ed.), The Breakout: The Origins of Civilization. Cambridge, Mass.: Peabody Museum, pp. 13-24.

November 18, 2009

A False Choice: Reductionism or Dualism

Twenty-four hundred years ago, Plato fired the first shot across the bow in the debate that – to this very day – structures how we view our world. He was arguing against the earliest known thinkers of the classical Greek world called the Presocratic philosophers, some of whom had come up with notions that we would regard as quite modern even today: for example, that the whole cosmos can be broken down to tiny particles of atoms, colliding mechanically with each other.

Plato hated this so much that he proposed five years of solitary confinement for people who held these opinions, followed by death if they hadn’t reformed. What got Plato so riled up? It was, in his own words, the notion that:

By nature and by chance, they say, fire and water and earth and air all exist – none of them exist by art – and … the earth, the sun, the moon and the stars were generated by these totally soulless means… not by intelligence, they say, nor by a god, nor by art, but … by nature and by chance.[1]

Plato was railing against the mindset that’s currently known as “reductionism” – the notion that everything in the universe, no matter how complex, mysterious or spiritual it might seem – can be theoretically reduced into a series of “nothing but” descriptions: nothing but atoms, nothing but neurons, nothing but genes. And Plato’s response to this was, again, something very familiar to us: he posited another dimension, a dimension of the soul, a dimension of eternal ideals, which existed apart from the material, everyday world, and somehow infused it with meaning and spirit. This is the Platonic dualism which underlies our Western tradition of thought (discussed in another post).

Many people still accept the prevailing dualism and lock into the construct of an external God and an immortal soul within us which will join Him in heaven some day. But this belief structure is under ever increasing empirical pressure from a scientific methodology that scans the brain and finds no place for the immortal soul, that scans the universe and finds no place for God.

Consequently, many others in today’s world have switched to the reductionism of science, summarized so clearly by Francis Crick, the co-discoverer of the DNA molecule:

You, your joys and your sorrows, your memories and your ambitions, your sense of personal identity and free will, are in fact no more than the behavior of a vast assembly of nerve cells and their associated molecules.[2]

But this approach delivers a world devoid of meaning, as described by Nobel Prize-winning physicist Steven Weinberg: “The more we know of the universe, the more meaningless it appears.”[3]

No wonder that so many of us would empathize with the deeply felt existential longing of biologist Ursula Goodenough, as she confides her inner fears:

… all of us, and scientists are no exception, are vulnerable to the existential shudder that leaves us wishing that the foundations of life were something other than just so much biochemistry and biophysics… My body is some 10 trillion cells. Period. My thoughts are a lot of electricity flowing along a lot of membrane. My emotions are the result of neurotransmitters squirting on my brain cells. I look in the mirror and see the mortality and I find myself fearful, yearning for less knowledge, yearning to believe that I have a soul that will go to heaven and soar with the angels.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. I believe that the choice between reductionism and dualism is a false choice. I propose that it’s perfectly possible to embrace both science and spirituality. The premise underlying this proposal is that the coldly mechanical universe offered by reductionist science is plain wrong: it’s a simplifying metaphor that’s proven very powerful as a way to analyze and predict elements of the natural world. But it’s no more than a metaphor and its simplifying assumptions are beginning to limit what science can offer us in the 21st century and beyond.

In order to understand reductionism a little better, I’m going to look at the three leading versions of it in today’s world, which I call genetic reductionism, neurological reductionism, and spiritual reductionism.[4]

The great popularizer of genetic reductionism is biologist Richard Dawkins, author of the best-seller The Selfish Gene. As Dawkins describes it, genes are the irreducible unit of biological replication. Genes are virtually immortal, and they use our bodies as the vehicle for their “selfish” purpose of replication:

… they swarm in huge colonies, safe inside gigantic lumbering robots, sealed off from the outside world… manipulating it by remote control. They are in you and in me; they created us, body and mind; and their preservation is the ultimate rationale for our existence.[5]

For Dawkins and his followers, all evolution can be explained by the underlying power of the “selfish gene.” But a growing number of biologists are showing that the selfish gene is, in fact, nothing more than a simplifying assumption, and an increasingly erroneous one, at that. “We have taken,” says biologist Richard Strohman, “a successful and extremely useful theory and paradigm of the gene and have illegitimately extended it as a paradigm of life.” “The mistaken idea,” he explains, is “that complex behavior may be traced solely to genetic agents and their surrogate proteins without recourse to the properties originating from the complex and nonlinear interactions of these agents.”[6]

Ultimately, as philosopher Evan Thompson points out, the obsessive focus on the selfish gene is such bad science, it doesn’t even deserve the name:

This notion of information as something that preexists its own expression in the cell, and that is not affected by the developmental matrix of the organism and environment, is a reification that has no explanatory value. It is informational idolatry and superstition, not science.[7]

What about neurological reductionism, the view summarized so well by Francis Crick, that “You’re nothing but a pack of neurons.”[8]? The problem with this approach is that it ignores the most salient aspect of our consciousness: its dynamic, ongoing self-organization. Even if you could map out every neuron in the brain and analyze each one, molecule by molecule, you wouldn’t even come close to explaining consciousness, because it’s the complex, dynamic patterns formed by their interactions that cause us to be who we are. “In cognitive neuroscience,” writes neurobiologist A.K. Engel, “we are witnessing a fundamental paradigm shift.” Classical views of the mind as a passively programmed computer are inconsistent with modern findings. “Current approaches emphasize the intimate relationship between cognition and action that is apparent in the real-world interactions of the brain and the rich dynamics of neuronal networks.”[9]

Mind is not the “pack of neurons” described by Crick and others. It’s only when we try to understand it for what it is, “a spatiotemporal pattern that molds the … dynamic patterns of the brain,”[10] that we can make real progress. As neuroscientist Scott Kelso puts it: “Instead of trying to reduce biology and psychology to chemistry and physics, the task now is to extend our physical understanding of the organization of living things.”[11]

Which takes us to spiritual reductionism, the dead-end view described by Nobel Prize-winner Roger Sperry that “man is nothing but a material object, having none but physical properties” and therefore “Science can give a complete account of man in purely physicochemical terms.”[12] What this view misses is the same principle that the other two forms of reductionism also miss: that we can only begin to understand the nature of complex systems – cells, organisms, even consciousness – when we focus on the ongoing, dynamic patterns of interactivity formed by these systems, rather than just the molecules, neurons and genes of which these systems are composed.

And when you begin looking at these interactions, something transformative happens: the emergent patterns caused by these complex systems affect the very system itself, causing an even greater spiraling of complexity. This is known as “circular causality” or “downward causation.” Biologist Brian Goodwin summarizes this dynamic as follows:

The important properties of these complex systems are found less in what they are made of than in the way the parts are related to one another and the dynamic organization of the whole – their relational order… To understand these complex nonlinear dynamic systems it is necessary to study both the whole and its parts, and to be prepared for surprises due to the emergence of unexpected behavior… In this sense the study of complex systems goes beyond reductionism, which focuses on the analysis of the components out of which a system is made.[13]

There are still many scientists, grounded in reductionist thinking, who like to dismiss these approaches as somehow unscientific or even “mystical”. That’s getting to be an increasingly difficult position to hold, as more and more scientific fields embrace the approaches of dynamical complexity theory to make inroads into their thorniest problems. Solé & Goodwin describe the current situation:

The concept of emergence, once regarded by many biologists as a vague and mystical concept with dangerous vitalist connotations, is now the central focus of the sciences of complexity. Here the question is, How can systems made up of components whose properties we understand well give rise to phenomena that are quite unexpected? Life is the most dramatic manifestation of this process, the domain of emergence par excellence. But the new sciences unite biology with physics in a manner that allows us to see the creative fabric of natural process as a single dynamic unfolding.

-Solé, R., and Goodwin, B. (2000). Signs of Life: How Complexity Pervades Biology, New York: Basic Books.

Reductionism, in its falsely compelling rigor, tells us “we’re all just nothing but… and that’s all there is.” Dualism, in contrast, posits an entirely different dimension of divinity and soul, and gives us the choice of taking it on faith, or falling back to the hard, cold ground of reductionism. However, when the full implications of the dynamics of complexity and emergence are understood, then, in the words of Roger Sperry, “the very nature of science itself is changed.” Science no longer needs to be the voice of spiritual despair. When science embraces dynamic complexity, as Sperry elaborates:

In the eyes of science… man’s creator becomes the vast interwoven fabric of all evolving nature, a tremendously complex concept that includes all the immutable and emergent forces of cosmic causation that control everything from high-energy subnuclear particles to galaxies, not forgetting the causal properties that govern brain function and behavior at individual and social levels.[14]

“Thus we have,” says complexity theorist Stuart Kauffman, “the first glimmerings of a new scientific worldview, beyond reductionism. In our universe emergence is real, and there is ceaseless, stunning creativity that has given rise to our biosphere, our humanity, and our history. We are partial co-creators of this emergent creativity.”[15]

I’m going to explore this theme, which I think will be central to the search for authentic meaning in the 21st century, in the sister blog to this one, called Finding the Li. In the meantime, I’ll leave you with a thought from Heraclitus, perhaps the first Western complexity theorist and ironically one of those Presocratic philosophers that Plato wanted to throw in jail:

For wisdom consists in one thing, to know the principle by which all things are steered through all things.[16]

[1] Cited in Vlastos, G. (1975/2005). Plato’s Universe, Canada: Parmenides Publishing, pp. 23-4

[2] Crick, F., (1995), Astonishing Hypothesis: The Scientific Search for the Soul. Scribner.

[3] Quoted by Kauffman, S., (2008). Reinventing the Sacred: A New View of Science, Reason, and Religion. New York: Basic Books.

[4] Ironically, the original form of reductionism from physics, “we’re all nothing but atoms”, has dissolved in the quagmire of “spooky” quantum mechanics and string theory, only to re-emerge in the biological sciences. For a history of this shift, see Woese, C. R. (2004). “A New Biology for a New Century”. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, pp. 173-186.

[5] Dawkins, R. (1976/2006). The Selfish Gene. New York: Oxford University Press.

[6] Strohman, R. C. (1997). “The coming Kuhnian revolution in biology.” Nature Biotechnology, 15(March 1997), 194-200.

[7] Thompson, E. (2007). Mind in Life: Biology, Phenomenology, and the Sciences of Mind, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

[8] Crick, F., (1995) op. cit.

[9] Engel, A. K., Fries, P., and Singer, W. (2001). “Dynamic Predictions: Oscillations and Synchrony in Top-Down Processing.” Nature Reviews: Neuroscience, 2(October 2001), 704-716.

[10] Kelso, J. A. S. (1995). Dynamic Patterns: The Self-Organization of Brain and Behavior, Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

[11] Kelso, op. cit.

[12] Sperry, R. W. (1980). “Mind-Brain Interaction: Mentalism, Yes; Dualism, No.” Neuroscience, 5(1980), 195-206.

[13] Goodwin, B. (2001). How the Leopard changed Its Spots: The Evolution of Complexity, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[14] Sperry, R. W. (1981). “Changing Priorities.” Annual Review of Neuroscience, 1981(4), 1-15.

[15] Kauffman, S. (2007). “Beyond Reductionism: Reinventing the Sacred.” Zygon, 903-14.

[16] Cited by Marlow, A. N. (1954). “Hinduism and Buddhism in Greek Philosophy.” Philosophy East and West, 4(1:April 1954), 35-45.

October 29, 2009

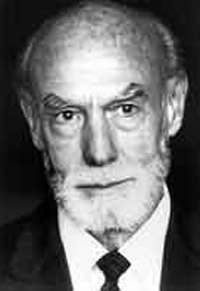

Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many

Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many

Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many

By Erik Hornung

New York: Cornell University Press

Erik Hornung is one of the great modern Egyptologists, and this book is probably his most important. However, it’s a fairly dense read, and I would recommend Jan Assmann’s The Search for God in Ancient Egypt, (written around the same time in the early 1980’s), as a more accessible in-depth view into ancient Egyptian thought.

Still, Hornung is clearly expert in his knowledge and applies it with a subtle mind. His primary purpose seems to be to argue against previous generations of Egyptologists who thought they saw a monotheistic cognitive framework in ancient Egyptian thought. Hornung’s argument is that, in fact, Egyptian cosmological thinking was polytheistic in its very essence. He believes that it’s easy to misinterpret many Egyptian invocations to gods that, in effect, flatter the god in question by asserting that he’s “the only one.” It’s a little like someone saying to his/her lover “To me, you’re everything.” That’s not a statement you’re meant to take literally, but it can still be true on a different level.

Hornung, however, goes well beyond that particular point. He describes Egyptian thought as pre-logical, a mode of cognition where if something is a, that doesn’t mean that it’s not also b. This, he argues, is a mode of thought that’s virtually unattainable for Western minds brought up on Aristotelian logic. If we could get there, he claims,

we shall be able to comprehend the one and the many as complementary propositions, whose truth values within a many-valued logic are not mutually exclusive, but contribute together to the whole truth: god is a unity in worship and revelation, and multiple in nature and manifestation.

That is, a god can be the only one in the cosmos, and at the same time be one of many. Consequently, Hornung sees monotheism, not as a stage along a continuum from polytheism, but as a “transformation”, accompanying the cognitive revolution to Aristotelian-style logic, a world of binary opposites, where the answer can be “yes” or “no” but not “yes and no.”

Although Assmann states that he disagrees with Hornung’s view of Egyptian polytheistic thought, I see their views as largely compatible. They both discuss the Akhenaten revolution – the short-lived imposition of true monotheistic worship on Egypt – as a hiatus utterly incompatible with the Egyptian worldview. But more than that, I think Hornung’s view of monotheism as a “conceptual transformation” fits in with Assmann’s view of the transition in Egypt’s history towards a kind of “cognitive dissonance”, with a “pantheistic theology of transcendence” which set the stage for later monotheistic thought. Under Assmann’s model, we’re still looking at a complete transformation between polytheism and monotheism – Assmann, in my view, goes further than Hornung by describing the transformative phase of post-Amarna Egyptian cosmology.

The most valuable take-away I get from Hornung is his emphasis on seeing the shift from polytheism to monotheism as a transformative stage in human consciousness. As he says, “Both of these worlds are consistent within their own terms of reference, but neither transcends historical space or can claim absolute validity.” I think this is an important frame of reference, which I elsewhere categorize by stages of the pfc’s advance in its power over human consciousness. In my categorization, there’s another shift from monotheism to scientific method, which has taken place over the past few hundred years. And most importantly, I think our world is ready for the next stage in the development of our global consciousness. But, that’s all material for another post…

October 22, 2009

The Pfc’s Coup: Monotheism

In my last post, The Rise of Dualism, I described how Plato and his Neoplatonic followers embedded the notion of body/soul dualism deep in the bedrock of Western thought.

From Plato’s time, our Western tradition of thought has consequently been structured by a cascade of dualities: mind/body; soul/body; eternal life in heaven/temporary life on earth; reason/emotion; man/nature. These dualities are fundamental to the way we think.

But it was when Christianity arose, merging the Hebrew idea of an omnipotent God with Plato’s idea of the abstract Good, that the pfc was able to take virtually total control of human consciousness. In the first few centuries of our common era, as Christianity pervaded Western thought, the dualism first conceived by Plato became the only acceptable view of existence.

Mosaic of Saint Paul (from the Vatican)

Our bodies became vessels of evil. In the words of St. Paul, “Flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God.”[1] Or as the Book of John says: “he that hateth his life in this world shall keep it unto life eternal.”[2] And the hatred of the material world, combined with a love for eternal salvation, continued unremittingly down the generations. The Cloud of Unknowing, a highly regarded spiritual text of the 14th century, describes the body as a “foul stinking lump”:

For as oft as [the soul] would have a true knowing and a feeling of his God in purity of spirit… he findeth evermore his knowing and his feeling as it were occupied and filled with a foul stinking lump of himself, the which must always be hated and despised and forsaken, if he shall be God’s perfect disciple.[3]

Hundreds of years later, New England clergyman, Cotton Mather was urinating against a wall and was disgusted by the sight of a dog relieving himself too. He came up with a unique response:

Thought I; ‘What mean and vile things are the children of men… How much do our natural necessities debase us, and place us… on the same level with the very dogs.’

My thought proceeded. ‘Yet I will be a more noble creature; and at the very time when my natural necessities debase me into the condition of the beast, my spirit shall (I say at that very time!) rise and soar’…

Accordingly, I resolved that it should be my ordinary practice, whenever I step to answer one or the other necessity of nature to make it an opportunity of shaping in my mind some holy, noble, divine thought…”[4]

The examples are endless. For over a thousand years, people of European descent thought of themselves as a “strange hybrid monster”[5] composed of two disconnected parts, a soul and a body, fighting against each other.

Rene Descartes, 1596-1650

This culminated in the seventeenth century, when the philosopher René Descartes who, after Plato, has probably had a greater impact than any other philosopher on modern Western thought, transformed this dualism into a form that would work for the modern world, with his famous conception of “cogito ergo sum” – “I think therefore I am”. Only our thought was truly reliable. Our sensations couldn’t be trusted. In Descartes’ own words “there is nothing included in the concept of body that belongs to the mind; and nothing in that of the mind that belongs to the body.”[6] The body was just a machine that wore out, a temporary abode for the immortal soul.

God granting dominion over Nature to Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden

And if the body were just a machine, then it followed that animals were nothing other than machines, because they didn’t have human souls within them. In fact, all of Nature was just a machine. A machine that’s there for the purposes of mankind, since didn’t God say in Genesis that Man shall “have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth”?[7]

This is what I mean by the pfc’s coup. First, Plato established the idea of the pfc’s conceptualization function as a separate dimension existing in its own image: an eternal world of abstraction. Next, the rise of Christianity gave a name to that abstraction – God – and assigned it infinite, universal power. Finally, the pfc (although of course it wasn’t known by that name) was identified as the only part of each human being that could connect with that infinite power – the abstracting mind, the immortal soul.

And now that this dualism was firmly established, everything else was fair game. Nature was there to be used for our purposes. Other peoples needed to be conquered in order to save their infinite souls that they didn’t even know they had.

In my next post, I’ll look at how the the rise of science permitted the pfc to expand its power even further – establishing a true tyranny over our consciousness.

[1] I Corinthians 15:50

[2] Book of John, 12:25

[3] Quoted in Huxley, A. (1945/2004). The Perennial Philosophy, New York: HarperCollins, p. 37

[4] Quoted in Orians, G. H. (2008). “Nature & human nature.” Dædalus(Spring 2008), 39-48. (p. 40)

[5] Lovejoy, A.O., ([1936] 1964). The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[6] Quoted by Capra, F., (1982/1988). The Turning Point: Science, Society, and the Rising Culture. New York: Bantam Books.

[7] Genesis, 1:26